According to the CDC, more than 28,000 people died of opioid overdose in the United States in 2014.

Many people in Greenville County are affected by opioid addiction, whether because of a family member, an employee, a friend, or their own struggle.

Rich Jones, Executive Director of FAVOR Greenville, pointed out that even if someone hasn’t personally experienced the impact of opioid addiction, they are experiencing its ripple effects on our society.

The already-stressed child welfare system in our state is now becoming burdened as addicted parents can no longer care for children.

Goldman Sachs says that the economy is slowing as workers who worry about addicted family members lose productivity and as potential employees are unable to pass pre-employment drug tests (particularly challenging for businesses in our near-zero unemployment rate economy).

Health care costs due to treatment and overdose are skyrocketing. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates them to be $20 million annually for just hospital inpatient and emergency department treatment, let alone the greater costs to communities.

Schools are dealing with students using opioid and the emotional repercussions students experience when their parents are addicted and non-functioning.

But as the epidemic of opioid addiction sweeps the nation and begins to take hold in the Southeast (the region where it has been last to arrive), Jones reports that people seem to be desensitized to the issue.

What do the data say about the unique nature of opioid addiction as compared to alcohol or other drugs? How are local nonprofits, health care providers, and law enforcement partnering in unique ways to address the epidemic, and what can funders do? The September 2017 meeting of Greenville Partnership for Philanthropy addressed the topic of opioids to a filled-to-capacity meeting room at FAVOR Greenville.

Jones reported that 106 people were coded as dying of an overdose in Greenville County in 2015 (although actual numbers were likely higher), and 179 people die of an overdose every day nationwide. Overdose now tops the chart of causes of accidental death in the United States. If we do nothing to address the trends, it is predicted that we’ll see a 187% increase in overdose deaths by 2027 – which would equal 93,000 people per year – far more than the AIDS epidemic, which peaked at 45,000 deaths annually.

Sheriff’s office representatives shared that Greenville County is on track to lead the state in overdose deaths for 2017 (Horry County topped the list in 2016), possibly because of the influx of new residents and a desensitization to the recreational use of opioids.

But they believe there is a difference in Greenville County’s opioid trends from other communities: in other states, the influx often begins with adults who receive a prescription for an injury or surgery and then become addicted, move to doctor-shopping for pills, and then to heroin. But in Greenville County, it appears to be youth on the leading edge of opioid addiction.

Representatives from the sheriff’s office believe this has a lot to do with affluence and desensitization. Students receive a prescription from oral surgery, or they take pills from their parents’ medicine cabinets, and then they swap them at parties. Because it originally came from a physician and the corner pharmacy (or at least teens perceive it to be so), it seems harmless. This opens the door to addiction.

Jones confirms this progression of addiction among young people. First, they often orally ingest prescription pain medication (“My friend got it from the medicine cabinet. It came from the doctor, so it can’t hurt you”). But when the effects of that are no longer as potent, someone suggests they crush the pill and snort it. After some time, the pills are no longer affordable or accessible, so heroin becomes a much cheaper option – but most affluent high schoolers would never go from drug store pills to intravenous use of a street drug. So they snort the heroin. But after a time, that becomes less potent – so a “friend” teaches them how to shoot it intravenously.

And this is how Greenville County and the rest of the Southeast joins Appalachia, New England, and the nation in the opioid epidemic.

How did the spread of opioid addiction first take root? Of course, there is no one cause. But several factors were identified.

Jones noted the marketing of OxyContin by Purdue Pharmaceuticals in the 1990s for long term use for chronic pain based on only limited research. Their heavy marketing techniques and the way they shifted the conversation around “pain management” is well-documented in books such as Barry Meier’s Pain Killer. The result is that in some states – including South Carolina – there are more prescriptions written for painkillers than there are people.

Dr. Lauren Demosthenes, faculty member with University of South Carolina School of Medicine – Greenville said that hospitals and health care providers were initially encouraged to attempt to eradicate pain for their patients. This was at a time when they believed that opioids were not addictive. Physicians are now much more aware of the addictive properties of opioids and are striving to help patients understand this as they care for them. The system, however, makes this a bit complicated as Se reimbursement is partially linked to patient satisfaction, and patients are more satisfied when they do not have pain. Medical students are being taught to think of non opioid alternatives for pain management. Several GPP members noted that they’d received seemingly large quantities of pills when discharged for surgery, which their prescribing physicians told them to “hold on to in case you have back trouble.”

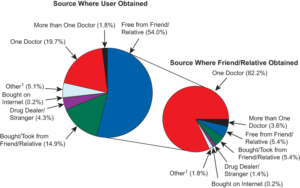

Jones presented data showing that the majority of opioid users obtained their pills from a friend or family member, and that the majority of those friends or family members obtained those pills from one doctor. So the notion that most users are doctor shopping or purchasing them illegally from dealers is inaccurate. It’s a serious problem, he says, operating within a system that is legal, well-funded, and accepted.

Fortunately, FAVOR Greenville, law enforcement, health care providers, and other treatment providers and community based organizations are working in new and creative ways to address opioids in Greenville County before they become the tragedy they are in other parts of the nation. Last year, 721 doses of Narcan were administered in Greenville County by law enforcement or health care providers to prevent death by overdose. The bigger question is how to turn that prevented death into a recovered life.

Jones contends that traditional approaches to treatment aren’t typically effective in addressing opioid addiction. The notion that we should wait for someone to hit rock bottom and acknowledge, then, that they need help is fundamentally flawed, he says, because their very addiction makes them unable to recognize their own need for treatment. He shared data that opioid users enter treatment an average of eight times before remaining abstinent. With this in mind, FAVOR’s approach is that the professional organization bears the responsibility to engage with the participant and his or her family, meeting the addict with treatment wherever he or she is – even if it’s on a basketball court, in front of a video game, or over a cup of coffee.

Dr. Demosthenes agrees that considering addiction treatment from a moral point of view is misguided. “If someone came in with a heart blockage, we wouldn’t put in stents to save their life and then send them out on the street and say, ‘Good luck with that chronic condition that got you here,’” she said. “We’d treat the whole person with lifestyle support, with medication, with counseling, with whatever’s needed for them to be healthy. We wouldn’t not help them because they failed in some way to end up with diabetes or heart disease. So why do we do this with addiction?”

FAVOR does this with a cadre of professional partners and volunteers and works to strike while the iron is hot. Captain Stacey Owens with the City of Greenville Police Department told the audience that they use Narcan to treat individuals who have overdosed and that Narcan has saved many lives since the Greenville Police Department began using it. However, the challenge for law enforcement is some of the individuals who have overdosed continue to use, and law enforcement are using Narcan multiple times on the same users. It became clear to law enforcement and FAVOR that follow up treatment has not been accessed by the addict.

Now, thanks to FAVOR, Rich Jones and his team started Operation Rescue providing 24-hour on-call assistance for people struggling with addiction. So, when the police administer Narcan, they also saturate the area with Operation Rescue cards that provide information about FAVOR, encouraging friends and family to seek help for the addict and for themselves. It has been a great partnership and has been a way to empower law enforcement to make the connection to longer term solutions. Police officers can pass these cards out to any family member, friends, or those who use heroin/opioids who want to seek help or guidance on how to get help.

Dr. Demosthenes also highlighted a partnership forged by a medical student who noted that infectious disease patients were spending weeks at Greenville Memorial Hospital being treated for infections due to intravenous drug use, but they were receiving less than optimal treatment for their underlying addiction while there. Social workers were helping as best they could, but opportunities to follow up to treat addiction were lacking. The department of internal medicine and FAVOR are now collaborating on a plan to provide coaching for these patients while in the hospital (while also training medical students on how to look for and deal with addiction in patients). This will hopefully help more patients find treatment and support systems for their substance misuse problem after they are discharged.

All agreed the only way to beat this epidemic is by uniting and communicating with each other.

How can funders make an impact? The panelists involved agreed that this is a challenging issue that needs to be attacked from all fronts: advocacy and policy change, education, treatment, recovery support, awareness, and more. Much of it has to do with rethinking the paradigm of treatment and of building connections between organizations to better support those who are addicted. This can be philanthropy’s sweet spot – funding innovation, encouraging partnership, and advocating for policy and paradigm change.

Learn and read more:

Rich Jones’ full PowerPoint presentation

Chronicle: State of Addiction – WYFF program

* chart source: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.htm#fig2.16